Cheah Cheng Hye: Malaysians should find this campaign of special interest because China, like Malaysia, is trying to break out of the “middle income trap”, a phenomenon faced by much of the developing world. Although Malaysia and China are different in many respects, they do share a common feature: an almost identical level of average incomes.

CHINA has launched a new campaign, called “Common Prosperity”, to improve the living standards of its people and make its society fairer.

Malaysians should find this campaign of special interest because China, like Malaysia, is trying to break out of the “middle income trap”, a phenomenon faced by much of the developing world.

Although Malaysia and China are different in many respects, they do share a common feature: an almost identical level of average incomes.

According to the World Bank, per capita gross domestic product in Malaysia and China were US$10,402 (RM43,517) and US$10,500 (RM43,927), respectively, in 2020. Thus, both are currently middle-income countries seeking to achieve developed-nation status in the medium-term future.

China’s plan is based largely on enlarging its middle class, by creating opportunities for the lower-income people, who currently make up a majority of its population, to become more productive and earn higher incomes.

ADVERTISING

Already, China, with a population of 1.4 billion, has 340 million middle-class people, larger than the entire population of the United States. Some estimates put the Chinese middle class at more than 400 million, using a looser definition of “middle class” status.

Beijing aims to increase the middle class to 500 million by 2025 and about 750 million by 2035. Put another way, Beijing is looking for roughly half the mainland Chinese population to be middle class by 2035, compared with less than 30% today, using a conservative definition.To realise the plan, the Chinese economy will need to double in size by 2035, having just doubled from 2010 to 2021.

In recent months, the Common Prosperity plan has caused concern among some investors, who worry that it is a kind of “Robin Hood” campaign. This is simply wrong. One only has to look at the “Zhejiang Plan”, announced in mid-2021, to get a detailed picture.

Zhejiang province (population: 65 million), located in the Yangtze River delta in central China, has set 52 performance targets to achieve Common Prosperity. The government has stated that Zhejiang is a “demonstration zone”, intended as a model for the nation.

Investors can rest assured.

The plan supports private enterprise, innovation, market development and small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

The plan takes aim against monopolistic business practices, supports the concept of a level playing field in the economy and aims to deflate the real estate market.

As officials have repeatedly stated, the overall objective is to create a society that is olive shaped, not pyramid shaped.

The plan does not emphasise wealth distribution but aims to make society more productive and fairer, with measures added to promote social mobility and better welfare for the needy. It confirms that Beijing remains committed to “state capitalism” (a Chinese version of the concept of “stakeholder capitalism”, currently gaining support in the West).

Clearly, the market-opening, pro-business reforms of the past four decades are irreversible.

Currently, the private sector (China has about 40 million SMEs) provides 50% of tax revenues, 60% of gross domestic product, 70% of patent filings and more than 80% of urban employment.

China’s domestic stock market, which trades through exchanges in Shanghai, Shenzhen and Beijing, is today the world’s most active, with a daily trading volume about four times that of second place New York. Indeed, there is no turning back the clock on using capitalism to help socialism.

Over the past several months, Beijing has launched restrictive regulations against Internet platforms, property developers, after-school tutoring and so on. These are aimed at problems that can’t wait for longer-term solutions.

But the reality of Common Prosperity is that it is mainly about long-term structural reforms to create a more sustainable and inclusive society. President Xi Jinping himself has stated that the objectives will take decades to achieve.

Over time, stock markets and other capital markets are to be encouraged so that more savings can be channelled into manufacturing, innovation and green energy. Real estate development is a different matter. The government is sticking to its restrictions on real-estate investments as housing seems over-built and bubbles have formed.

So, will it work?

The Chinese public, it seems, is confident that Common Prosperity targets can be achieved, given the party’s strong track record, with 800 million people – roughly 10% of the global population – lifted out of extreme poverty over the past four decades.

Indeed, China has already come a long way; as recently as the early 1960s, parts of the country suffered from starvation.

But the obstacles to Common Prosperity cannot be under-estimated, ranging from geo-political tensions to an ageing population and the overheated property market.

Undoubtedly, Common Prosperity represents a shift leftwards in Chinese politics, after decades of liberal policies that enabled a privileged few to make a lot of money. Capital flight could become a persistent problem for China (as it is for Malaysia) as the rich move money to offshore shelters.

Furthermore, for Beijing, real estate is a particularly difficult balancing act, as the property sector represents about 25% of the Chinese economy and 40% of people’s savings.

In urban areas, 80% of households already own their own property, and 40% have second homes. Home prices are up 50% over the past decade.

The property boom is financed by heavy debts, putting financial stability at risk. Beijing has to find ways to cool down the property sector but avoid a hard landing for house prices.

China’s ageing population, too, is a headwind.

But the impact can be offset by improving productivity and innovation.

Here, China’s great success in education is helpful. Each year, China produces more than nine million university graduates, exceeding the combined total of the United States, Britain, Germany, Japan and South Korea. The Chinese graduates are concentrated in science, math and engineering.

In addition, about five million people complete vocational school each year with technical and trade skills. Chinese talent is on an upward spiral, meaning many problems can be overcome.

Common Prosperity is driven by the Communist Party of China, which has been in power since 1949, and has always identified itself as a party representing workers and peasants.

But now, the party has staked its brand on the success of the prosperity plan and in the process, it is transforming itself into a party for the middle class.

If successful, the party will lift China into the ranks of developed nations by 2035.

Datuk Seri Cheah Cheng Hye is the head of Value Partners Group, an asset management firm in Hong Kong. He is also an independent non-executive director of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Ltd. He started his career as a reporter in The Star.

Related News

China’s ‘Mr Income Distribution’ explains common prosperity

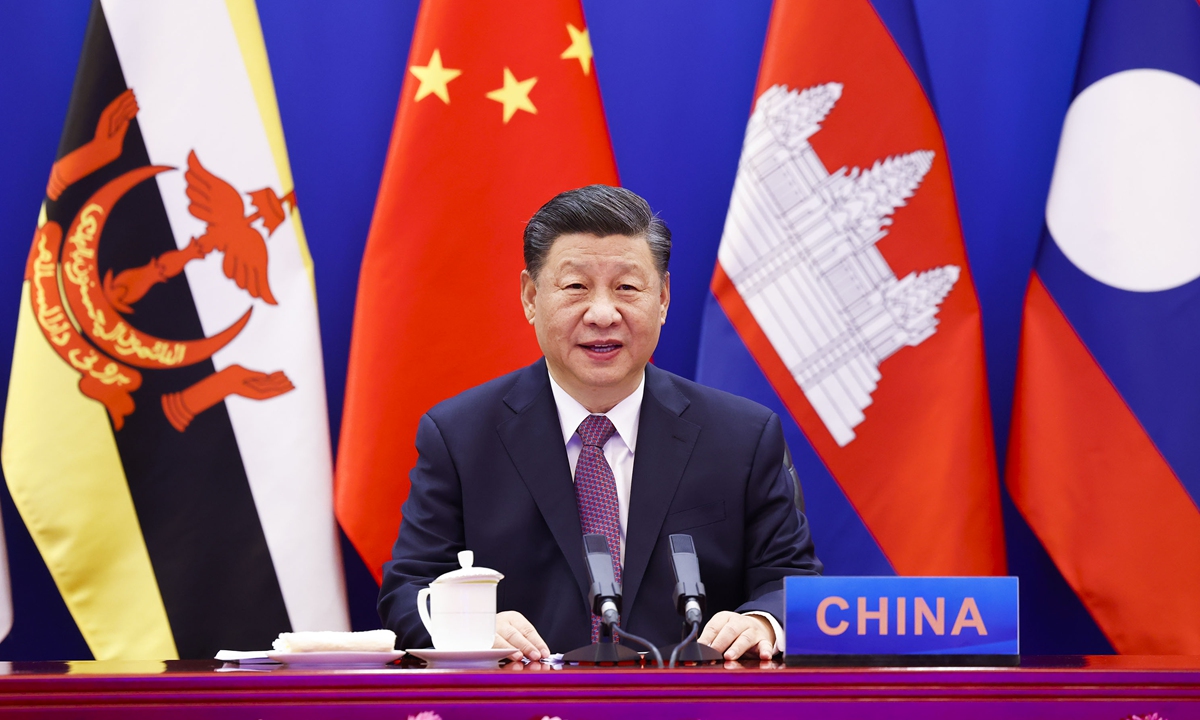

China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations decided to establish comprehensive strategic partnership on Monday, a new milestone in ...

Related posts:

Academics attribute China’s success to its highly-rated administrative system & strong governance as CPC celebrating the centenary

China has lifted 700 million out of poverty over 70 years, set to eliminate its last poor very soon

Decoding an awakening giant, the China's secret recipe

of success for an economic miracle

China needs strong core leadership: media survey

No comments:

Post a Comment