China’s search for technological mastery will succeed because it is essentially replicating the actual history of the economics and policies that led the United States to technological dominance, rather than the ideological history of what many Americans believe lies behind their success For years, American policymakers and pundits have believed China’s search for technological mastery or supremacy is doomed to fail or at least be consigned forever to mediocrity and also-ran status. This belief lies behind the strategy, first put forward by the Donald Trump administration, and now followed by Joe Biden’s White House, to restrict or ban the transfer of crucial technologies, notably the most advanced semiconductors and their production methods. And yet, paradoxically, China is bound to succeed, despite the inevitable hiccups and setbacks, because it is essentially replicating the actual history of the economics and policies that led the United States to technological dominance, rather than the ideological history of what many Americans believe lies behind their success. They have applied their own ideological models to predict China’s supposedly “inevitable” failure, instead of using their own actual history of American technology and science, and economic policy, to analyse China’s development and acquisition of key technologies in the 21st century. This is perhaps not surprising. Rich, powerful and successful people usually tell a different story about how they get to where they are to what actually happened to them. It’s human nature. China’s Great Firewall It’s generally believed that free enterprise is the necessary and sufficient condition for hi-tech industries. This means: the free flow of information and talent; open market; no or minimal government intervention, also called deregulation; and intellectual property rights protection. It’s believed only the market can choose winners and eliminate the losers, and that any state attempt to choose “national champions” is bound to fail and to be wasteful. China’s so-called Great Firewall of the internet stands as both an actual barrier and a potent symbol that is antithetical to all those fundamental neoliberal assumptions, which, granted, are being increasingly challenged and even undermined, even among some US professional economists and historians. However, if you believe in all those assumptions, you of course will logically argue that China is bound to fail. But is it? Let’s consider the historical reference: the Great Wall of China. It has been alternately argued that it was built to resist foreign invaders, and/or to keep in the domestic population. Either way, it was too porous to be truly effective.

A piece of Web3 tech helps banned books through the Great Firewall’s cracks

16 Apr 2022

The same argument has often been made about the ineffectiveness and absurdity of the Great Firewall. Many Chinese households can just get a VPN and then can pretty much access whatever they want from outside China. Yet, as it turns out, porousness or partial online filter and censorship, has been a godsend for Beijing’s industrial policy for hi-tech development. This is no doubt an unintended consequence, but once it has been realised, its value is deeply appreciated by the authorities. Incidentally, that’s why officials tolerate the widespread use of VPNs, despite occasional and ineffective crackdowns.

In China, for people who have the know-how, education or mere curiosity, they can easily bypass the Great Firewall for information to start a business, launch a research project or steal a foreign design. These are the people you need to be in hi-tech industries. Yet, for the vast majority of Chinese, access to contents outside China is still restricted.

China also restricts foreign business and informational access. It has banned such companies as Google, Facebook and Twitter. But of course, it welcomes companies such as Apple, Starbucks and Wall Street banks.

The Great Firewall serves as the online market barrier to foreign entry, or the internet moat to protect infant industries from foreign competition or business invasion; again, one of two functions of the ancient Great Wall.

Intellectual property theft

No one would argue intellectual property theft or industrial espionage is essential to the economic development of a country. However, many economic historians have pointed out that whether it was the rise of Elizabethan England, 19th century America, modern Japan and South Korea, or contemporary China, intellectual property theft and/or industrial espionage played a key role in their economic rise; and state industrial policy as well.

But a successful country doesn’t steal forever. Once it reaches a certain critical stage of hi-tech development, when it has amassed the talent, resources and facilities, it starts to innovate. Then, it starts developing and protecting its own intellectual property regime to prevent others from stealing -and of course, to complain about theft.

That’s the stage China is entering. According to the China National Intellectual Property Administration last month, 696,000 invention patents were authorised in 2021, an average of 7.5 of high-value patents per 10,000, or nearly double the ratio for 2017. Whether those patents were really as useful or original as they claimed is not the issue here, but rather that they show Chinese authorities are committed to intellectual property protection and building up a viable patent regime.

But, besides the obvious racism about the lack of Asian originality, the neoliberal set of assumptions that I referred to above tend to reinforce the idea that China’s political and economic systems can’t innovate and so must go on stealing. That is also related to what American historian Richard Hofstadter has called “the paranoid style” in US politics. Its most infamous manifestation was the anti-communist McCarthyism. Its most recent example is the FBI’s China Initiative, which targeted ethnic Chinese researchers, especially those in US universities.

China’s chip output shrinks as Covid-19 lockdowns paralyse industries

16 May 2022

The Silicon Valley folklore is that of a lone maverick who has a great idea and pushes it to fruition, and in the process, creates a multibillion-dollar industry. That cannot be further from the assumption behind Japanese-Korean-Chinese state industrial policy, according to which innovation is a collective enterprise, not one of individual genius or charisma. It’s all about the sustained commitment of public resources and collective talent between the state and the private sector.

It’s a common criticism that such a policy is wasteful; it often backs the wrong technologies and industries. That’s true. However, the Silicon Valley model is also prone to periodic market euphoria, mania, panic and crashes, from the dotcom implosion to the current ongoing crypto-crashes. I will leave it to economic historians and econometricians to determine whether the state or non-state model is more wasteful or destructive.

Conclusions

Belatedly, the Biden administration is slowly realising that whether it’s containment against China or competition with it, the horse has bolted out of the barn already. That is why despite its hostile rhetoric, it has no coherent policy on how to deter or delay China’s technological drive for mastery or supremacy. This conflict cuts to the very ideological self-beliefs of the two countries. Only time will tell how it will turn out.

However, restricting or banning technological transfer will not work. The great British historian Arnold Toynbee famously wrote that it was usually countries or civilisations confronted with great or even mortal challenges that prevailed and prospered in history, not those that were well-endowed with rich resources. Denying China access to vital technologies at this late stage will simply force it to develop its own domestic capabilities. That won’t make it weaker, only stronger and more self-reliant.

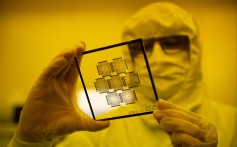

For years, American policymakers and pundits have believed China’s search for technological mastery or supremacy is doomed to fail or at least be consigned forever to mediocrity and also-ran status. This belief lies behind the strategy, first put forward by the Donald Trump administration, and now followed by Joe Biden’s White House, to restrict or ban the transfer of crucial technologies, notably the most advanced semiconductors and their production methods.

And yet, paradoxically, China is bound to succeed, despite the inevitable hiccups and setbacks, because it is essentially replicating the actual history of the economics and policies that led the United States to technological dominance, rather than the ideological history of what many Americans believe lies behind their success.

The Silicon Valley folklore is that of a lone maverick who has a great idea and pushes it to fruition, and in the process, creates a multibillion-dollar industry. That cannot be further from the assumption behind Japanese-Korean-Chinese state industrial policy, according to which innovation is a collective enterprise, not one of individual genius or charisma. It’s all about the sustained commitment of public resources and collective talent between the state and the private sector.

It’s a common criticism that such a policy is wasteful; it often backs the wrong technologies and industries. That’s true. However, the Silicon Valley model is also prone to periodic market euphoria, mania, panic and crashes, from the dotcom implosion to the current ongoing crypto-crashes. I will leave it to economic historians and econometricians to determine whether the state or non-state model is more wasteful or destructive.

Conclusions

Belatedly, the Biden administration is slowly realising that whether it’s containment against China or competition with it, the horse has bolted out of the barn already. That is why despite its hostile rhetoric, it has no coherent policy on how to deter or delay China’s technological drive for mastery or supremacy. This conflict cuts to the very ideological self-beliefs of the two countries. Only time will tell how it will turn out.

However, restricting or banning technological transfer will not work. The great British historian Arnold Toynbee famously wrote that it was usually countries or civilisations confronted with great or even mortal challenges that prevailed and prospered in history, not those that were well-endowed with rich resources. Denying China access to vital technologies at this late stage will simply force it to develop its own domestic capabilities. That won’t make it weaker, only stronger and more self-reliant.

For years, American policymakers and pundits have believed China’s search for technological mastery or supremacy is doomed to fail or at least be consigned forever to mediocrity and also-ran status. This belief lies behind the strategy, first put forward by the Donald Trump administration, and now followed by Joe Biden’s White House, to restrict or ban the transfer of crucial technologies, notably the most advanced semiconductors and their production methods.

And yet, paradoxically, China is bound to succeed, despite the inevitable hiccups and setbacks, because it is essentially replicating the actual history of the economics and policies that led the United States to technological dominance, rather than the ideological history of what many Americans believe lies behind their success.

They have applied their own ideological models to predict China’s supposedly “inevitable” failure, instead of using their own actual history of American technology and science, and economic policy, to analyse China’s development and acquisition of key technologies in the 21st century.

US cannot stop China's hi-tech rise | South China Morning Post

Alex Lo has been a Post columnist since 2012, covering major issues affecting Hong Kong and the rest of China. A journalist for 25 years, he has worked for various publications in Hong Kong and Toronto as a news reporter and editor. He has also lectured in journalism at the University of Hong Kong.

Related posts:

https://youtu.be/hRv0QMEwdas https://youtu.be/dtT0rHgJ9-I 《今日关注》是CCTV中文国际频道播出的时事述评栏目。该栏目紧密跟踪国内外重大新闻事件,邀请国内外一流的专家和高级官员梳理新闻来龙去脉,评论新闻事...

No comments:

Post a Comment